I first read Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises in an unknown time and place; my second reading took place in 2009 upon the recommendation of a friend; my third reading was for a graduate course as part of my Masters in Literature.

The novel focuses on a group of expats living in Europe in the 1920s as they travel around Paris and Spain in search of nothing more than a good time. Jake Barnes, the protagonist, is a war veteran come newspaperman who is in requited but unfulfilled love with Lady Brett Ashley. Through the story we see Jake and Brett commiserate on their untenable love while Brett blows her way through a handful of lovers, all while engaged to another man.

Lady Brett Ashley is an absolutely fascinating character to read. All of the twists and turns of the novel revolve around her, and yet it is Jake who narrates and centers the plot. Her personality and her behavior are all filtered through a man who loves but cannot possess her, and this removal presents a wonderful dilemma. Who is she really? At every read, I have developed different impressions of Lady Brett.

She is not the only enigma here. The characters here are all damaged, melancholic, and honestly tragic. Representative of the Lost Generation, they are all post-World War I young adults, unsure how to adapt to the new world. These characters inner demons drive them to a sort of ennui that I find a tad melodramatic at my current age. Still, their conflicting and crazy personalities are fascinating.

One nagging bit of the novel for me has to do with the barrier to Jake and Brett's love. It feels like a MacGuffin - something that seems remarkably important but in actuality is relatively, well, nothing. Read the novel and then come back and tell me what you think.

eclectic / eccentric

books, education, cooking, kids, & life

01 May 2020

02 September 2017

Blog for My Masters Thesis

If any of my awesome followers are still around, I wanted to direct you to a new blog I'm writing for my Master's thesis called Writing My Way In. If you're interested, head on over to check it out. I would love to hear your thoughts and have your support as I finish my second Master's degree - this time in Literature.

Also, you may or may not have noticed that my blog is no longer at http://www.eclectic-eccentric.com. I, unfortunately, did not get the email telling me to update my credit card expiration date, and as such I lost that domain name. The address is back to https://eclectcentric.blogspot.com/ so update your feeds if you are one of those patiently waiting for me to come back (thinking January 2018)

Miss you all!

Also, you may or may not have noticed that my blog is no longer at http://www.eclectic-eccentric.com. I, unfortunately, did not get the email telling me to update my credit card expiration date, and as such I lost that domain name. The address is back to https://eclectcentric.blogspot.com/ so update your feeds if you are one of those patiently waiting for me to come back (thinking January 2018)

Miss you all!

22 May 2016

BEA Spotlight: The People

I was very happy to get the chance to go to BEA this year. I went way back in 2010 - aka Pre-Kid Years - when I was in full blogging mode, and I fully intended on making it a yearly trip. Then the hubby and I decided to have some babies and that sort of took over my life between two miscarriages and then two pregnancies resulting in two small, needy children. Now the youngest is one and I'm ready to get back into the swing of things, and lucky me, BEA was in Chicago, a mere one hour drive (assuming no traffic) from where I live.

And even luckier me, I was finally going to meet some of my long-time blogging buddies: the awesome Jill of Rhapsody in Books and the equally awesome Sandy of (the blog formerly known as) You've Gotta Read This. Both of these women rock my world, and I was so happy to finally meet them after years ofonline stalking blogging romance friendship.

I also was lucky enough to meet up with Candace of Beth Fish Reads and Sheila of Book Journey, and I briefly saw Kim of Sophisticated Dorkiness, Florinda of 3R's Blog, and a handful of other bloggers that I'm not going to name because I just know I'm forgetting people.

For the first time, my real life people and my online people met. A fellow English teacher from my college, Jenny, came with me to BEA and meshed perfectly with the bloggers. Jenny and I also attended BookCon on Saturday. After three days of BEA and one day of BookCon, the two of us have reading material for the next five years. Posts on the books forthcoming.

I, sadly, took no pictures of this inspiring meeting of the minds. One picture I did get, however, is the following:

Believe it or not, that is my freshman year roommate Ann, a person I have not seen or had any contact with since 1998 when I left Illinois Wesleyan University to attend DePaul University after only a semester. That's right people NINETEEN NINETY EIGHT. Otherwise known as the last century. I remember quite a bit about our time together - she was (and is) a kind and interesting person - but what I remember the most is her passion for Buffy the Vampire Slayer and her creativity, both of which I very much appreciated then and now.

Our BEA meeting was quite random: I was coming back to the floor after my second book drop in the car, happily eating a banana, when the lovely woman holding open the door for me suddenly said, "Trisha?!?". Strange coincidence I tell you.

Speaking of bananas, I had an incident with a banana on Friday. I always carry one in my purse - I'm a mom - and it accidentally fell on the bathroom floor. The peeling was still perfectly in tact but I just couldn't bring myself to keep and eat the in-my-mind-disgustingly-tainted banana, so I threw it away. Many people I have told this story to said they would have peeled and eaten it. You?

Now I've told you a bit about the people I was privileged enough to spend some time with at BEA, so over the next week or so, I'll regale you with the books!

And even luckier me, I was finally going to meet some of my long-time blogging buddies: the awesome Jill of Rhapsody in Books and the equally awesome Sandy of (the blog formerly known as) You've Gotta Read This. Both of these women rock my world, and I was so happy to finally meet them after years of

I also was lucky enough to meet up with Candace of Beth Fish Reads and Sheila of Book Journey, and I briefly saw Kim of Sophisticated Dorkiness, Florinda of 3R's Blog, and a handful of other bloggers that I'm not going to name because I just know I'm forgetting people.

For the first time, my real life people and my online people met. A fellow English teacher from my college, Jenny, came with me to BEA and meshed perfectly with the bloggers. Jenny and I also attended BookCon on Saturday. After three days of BEA and one day of BookCon, the two of us have reading material for the next five years. Posts on the books forthcoming.

I, sadly, took no pictures of this inspiring meeting of the minds. One picture I did get, however, is the following:

Believe it or not, that is my freshman year roommate Ann, a person I have not seen or had any contact with since 1998 when I left Illinois Wesleyan University to attend DePaul University after only a semester. That's right people NINETEEN NINETY EIGHT. Otherwise known as the last century. I remember quite a bit about our time together - she was (and is) a kind and interesting person - but what I remember the most is her passion for Buffy the Vampire Slayer and her creativity, both of which I very much appreciated then and now.

Our BEA meeting was quite random: I was coming back to the floor after my second book drop in the car, happily eating a banana, when the lovely woman holding open the door for me suddenly said, "Trisha?!?". Strange coincidence I tell you.

Speaking of bananas, I had an incident with a banana on Friday. I always carry one in my purse - I'm a mom - and it accidentally fell on the bathroom floor. The peeling was still perfectly in tact but I just couldn't bring myself to keep and eat the in-my-mind-disgustingly-tainted banana, so I threw it away. Many people I have told this story to said they would have peeled and eaten it. You?

Now I've told you a bit about the people I was privileged enough to spend some time with at BEA, so over the next week or so, I'll regale you with the books!

19 May 2016

Is Villette "Feminist"?

In Charlotte Bronte's Villette, Lucy Snowe travels from her home to teach at a girls' school, and in so doing, finds herself. It's a rather ambiguous tale with a puzzling ending that focuses more on Lucy's inner workings than on her outer actions. Critics have focused on this psychological aspect of the text, but one issue really stands out: The question of whether Villette can be considered a feminist or anti-feminist text is complicated by multiple issues.

For me though, determining which side of the feminist line the text falls on requires a close reading of the text in light of a careful consideration of the environment in which the text was written. Evaluating the text from a contemporary understanding of gender is disingenuous and inauthentic.

According to Helen Davis, the ideological climate of nineteenth-century Britain restricted Bronte’s ability to push a direct feminist agenda; hence, the ambiguous nature of the text in regards to a feminist reading. Portraying an independent, professional woman was “restricted by both the social norms of the receiving community and by the textual practices of the genre” (Davis 201). In order to work around these restrictions, authors such as Bronte addressed the topics “in a way that retains discursive authority while still conveying the desired meaning” (Davis 201).

This delicate balancing act between revealing and concealing results in textual ambiguities “that arise from an author’s simultaneous urge to narrate possibilities outside of the boundaries of social norms while also conforming to social and narrative expectations sufficiently to create a text that can and will be successfully disseminated” (Davis 201-202). After all, you can’t influence the minds of a culture if no one is reading your novel. So “specific events, desires, and goals that are nonconforming within the receiving community are often incorporated ambiguously” (Davis 202) leaving the text open for varied critical interpretation.

One passage from the text that addresses a specific, nonconforming concept stood out to me:

“My time was now well and profitably filled up. What with teaching others and studying closely myself, I had hardly a spare moment. It was pleasant. I felt I was getting on; not lying the stagnant prey of mould and rust, but polishing my faculties and whetting them to a keen edge with constant use. Experience of a certain kind lay before me, on no narrow scale”. (Bronte)

Many upper-class women in the Victorian Age were confined to a domestic sphere that rarely needed their active attention in any profitable way; the suggestion being they were closer to the “stagnant prey of mould and rust” Bronte mentions in this passage, their mental faculties lying dormant except for the development and maintenance of profitable social connections. Here Lucy is thrilled to be both put to use and allowed experience, but her thoughts are entirely self-directed and any implication as to criticism of social constraints is made metaphorically, not directly.

In another section of the novel, Lucy is thrilled for the simple pleasure of walking alone: “to walk alone in London seemed of itself an adventure…to do this, and to do it utterly alone, gave me, perhaps an irrational, but a real pleasure” (Bronte). Here the Victorian restriction placed on women to always be “chaperoned” (i.e. surveilled) is addressed but with the caveat that Lucy’s pleasure is “perhaps irrational”.

Despite the ambiguities and caveats in the text as a whole, certain passages do reflect a directly feminist argument. For example, when speaking of Madame Beck, Lucy feels “that school offered her for her powers too limited a sphere; she ought to have swayed a nation: she should have been the leader of a turbulent legislative assembly” (Bronte). Madame Beck is restricted from participating in government by her gender, but Lucy directly states that’s where her talents would best serve.

Bronte does, ultimately, present a feminist perspective for her time. At the end of Villette, Lucy is “a single, successful businessperson, an identity that threatens her standing as a socially acceptable narrator and woman” (Davis 202). Her outcome provides a “different kind of success, one connected to ambition and independence” that is “not socially acceptable in the nineteenth century” (Davis 203). Bronte has set up a female role model, of sorts, for those women who searched for happiness outside of marriage. Unfortunately, Bronte has to temper Lucy’s independence and “in the interest of self-preservation, [Lucy] presents her success as the result of circumstance and others’ actions rather than the endpoint of her own active striving” (Davis 202). Lucy can’t “openly acknowledge her goals without alienating contemporary readers” (Davis 203).

I'm wondering if any of you see this in contemporary literature. What issues or perspectives do we water down in order to make it palatable to readers?

Works Cited

Bronte, Charlotte. Villette. Project Gutenberg. Web. 26 March 2016.

Davis, Helen. “I Seemed to Hold Two Lives”: Disclosing Circumnarration in Villette and The Picture of Dorien Gray”. Narrative 21.2 (May 2013): 198-220. Web. 29 March 2016.

For me though, determining which side of the feminist line the text falls on requires a close reading of the text in light of a careful consideration of the environment in which the text was written. Evaluating the text from a contemporary understanding of gender is disingenuous and inauthentic.

According to Helen Davis, the ideological climate of nineteenth-century Britain restricted Bronte’s ability to push a direct feminist agenda; hence, the ambiguous nature of the text in regards to a feminist reading. Portraying an independent, professional woman was “restricted by both the social norms of the receiving community and by the textual practices of the genre” (Davis 201). In order to work around these restrictions, authors such as Bronte addressed the topics “in a way that retains discursive authority while still conveying the desired meaning” (Davis 201).

This delicate balancing act between revealing and concealing results in textual ambiguities “that arise from an author’s simultaneous urge to narrate possibilities outside of the boundaries of social norms while also conforming to social and narrative expectations sufficiently to create a text that can and will be successfully disseminated” (Davis 201-202). After all, you can’t influence the minds of a culture if no one is reading your novel. So “specific events, desires, and goals that are nonconforming within the receiving community are often incorporated ambiguously” (Davis 202) leaving the text open for varied critical interpretation.

One passage from the text that addresses a specific, nonconforming concept stood out to me:

“My time was now well and profitably filled up. What with teaching others and studying closely myself, I had hardly a spare moment. It was pleasant. I felt I was getting on; not lying the stagnant prey of mould and rust, but polishing my faculties and whetting them to a keen edge with constant use. Experience of a certain kind lay before me, on no narrow scale”. (Bronte)

Many upper-class women in the Victorian Age were confined to a domestic sphere that rarely needed their active attention in any profitable way; the suggestion being they were closer to the “stagnant prey of mould and rust” Bronte mentions in this passage, their mental faculties lying dormant except for the development and maintenance of profitable social connections. Here Lucy is thrilled to be both put to use and allowed experience, but her thoughts are entirely self-directed and any implication as to criticism of social constraints is made metaphorically, not directly.

In another section of the novel, Lucy is thrilled for the simple pleasure of walking alone: “to walk alone in London seemed of itself an adventure…to do this, and to do it utterly alone, gave me, perhaps an irrational, but a real pleasure” (Bronte). Here the Victorian restriction placed on women to always be “chaperoned” (i.e. surveilled) is addressed but with the caveat that Lucy’s pleasure is “perhaps irrational”.

Despite the ambiguities and caveats in the text as a whole, certain passages do reflect a directly feminist argument. For example, when speaking of Madame Beck, Lucy feels “that school offered her for her powers too limited a sphere; she ought to have swayed a nation: she should have been the leader of a turbulent legislative assembly” (Bronte). Madame Beck is restricted from participating in government by her gender, but Lucy directly states that’s where her talents would best serve.

Bronte does, ultimately, present a feminist perspective for her time. At the end of Villette, Lucy is “a single, successful businessperson, an identity that threatens her standing as a socially acceptable narrator and woman” (Davis 202). Her outcome provides a “different kind of success, one connected to ambition and independence” that is “not socially acceptable in the nineteenth century” (Davis 203). Bronte has set up a female role model, of sorts, for those women who searched for happiness outside of marriage. Unfortunately, Bronte has to temper Lucy’s independence and “in the interest of self-preservation, [Lucy] presents her success as the result of circumstance and others’ actions rather than the endpoint of her own active striving” (Davis 202). Lucy can’t “openly acknowledge her goals without alienating contemporary readers” (Davis 203).

I'm wondering if any of you see this in contemporary literature. What issues or perspectives do we water down in order to make it palatable to readers?

Works Cited

Bronte, Charlotte. Villette. Project Gutenberg. Web. 26 March 2016.

Davis, Helen. “I Seemed to Hold Two Lives”: Disclosing Circumnarration in Villette and The Picture of Dorien Gray”. Narrative 21.2 (May 2013): 198-220. Web. 29 March 2016.

03 May 2016

Sartor Resartus and Permission to Doubt

David Amigoni, in Victorian Literature, remarks that Victorian society revolved around oppositions: rural and urban, modernity and historicity, progress and tradition, and science and faith (5-6). Continually stuck in a fight between opposing and contradictory ideologies, the Victorians were probably relieved by the permission to doubt granted them in Thomas Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus.

Sartor Resartus, often referred to as Thomas Carlyle’s “spiritual autobiography”, follows the main character, Diogenes, as he “gains an education steeped in the traditions of the Enlightenment which destroys his belief in revealed religion, but leaves him little or nothing positive to embrace” (Trela). All of this leads to a crisis of faith which we see in “The Everlasting No”. Diogenes goes through a period of doubt in “The Center of Indifference” but then he realizes that he must embrace the divinity of the universe as expressed in “The Everlasting Yea”. Diogenes's path, and much of his reasoning, mirrors that of Carlyle himself as he worked through his own crisis of faith (Trela). By putting his own spiritual journey out there, himself a great man known for his intellectualism and his faith, Carlyle gave Victorians permission to question the traditional views and dogma of established religions.

The argument Carlyle makes that might have helped allay Victorian anxiety is that doubt increases faith. Carlyle writes that readers can’t “call our Diogenes” wicked due to his crisis of faith because “unprofitable servants as we all are, perhaps at no era of his life was he more decisively the Servant of Goodness, the Servant of God, than even now when doubting God’s existence”. Carlyle contends that true faith requires challenge and that “a tearing down or questioning of the beliefs of one faith is in fact the preparation for a newer, richer, and truer form of belief in a new era” (Trela).

He gives Victorians permission to question their faith and to modify it for a new generation: “In every new era, too, such Solution comes out in different terms; and ever the Solution of the last era has become obsolete, and is found unserviceable. For it is man’s nature to change his Dialect from century to century; he cannot help it though he would” (Carlyle). Victorians embodied change and that spilled over into faith; as Amigoni states, “religious faith in a stable creation was never far from intellectual skepticism engendered by a sense of impermanence in Victorian society and culture” (Amigoni 6). For a society in the midst of tremendous change in all aspects of life, a society steeped in tradition, simultaneously hanging on to and rejecting ideologies of the past, permission to change must have been comforting.

Then again, even with the relieving messages in the text, Victorian society may not have benefitted from Sartor Resartus at all as it received a “bewildered reception with the audience of its day; neither Tories, Utilitarians, nor Whigs really understood it…due to Carlyle’s intentional disruption of the expectations of his British audience’s naïve realism” (Baker 225). Even if the text was understood by a broad audience, the Victorians never had a massive revival of faith, at least not to the “Everlasting Yea” extreme.

As with Victorian times, contemporary western societies may feel relief or even vindication at Carlyle’s contention that doubt is a path to a stronger faith. Doubt in a higher power permeates western culture as, again like with the Victorians, science continually answers those questions once put to God, and experience and humanity deny tenets of organized religious dogma once held fast. Also like the Victorians, contemporaries seem stuck at Doubt, never quite making it to the Everlasting Yea.

Works Cited

Amigoni, David. Victorian Literature. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011. Print.

Baker, Lee C. R. “The Open Secret of “Sartor Resartus”: Carlyle’s Method of Converting His Reader”. Studies in Philology 83.2 (Spring 1986): 218-235. Web. 8 Mar. 2016.

Carlyle, Thomas. Sartor Resartus. eBooks@Adelaide. The University of Adelaide. Web. 6 March 2016.

Trela, D.J. "Carlyle, Thomas 1795-1881." Encyclopedia of Life Writing: Autobiographical and Biographical Forms. Ed. Margaretta Jolly. London: Routledge, 2001. Credo Reference. Web. 8 Mar. 2016.

Sartor Resartus, often referred to as Thomas Carlyle’s “spiritual autobiography”, follows the main character, Diogenes, as he “gains an education steeped in the traditions of the Enlightenment which destroys his belief in revealed religion, but leaves him little or nothing positive to embrace” (Trela). All of this leads to a crisis of faith which we see in “The Everlasting No”. Diogenes goes through a period of doubt in “The Center of Indifference” but then he realizes that he must embrace the divinity of the universe as expressed in “The Everlasting Yea”. Diogenes's path, and much of his reasoning, mirrors that of Carlyle himself as he worked through his own crisis of faith (Trela). By putting his own spiritual journey out there, himself a great man known for his intellectualism and his faith, Carlyle gave Victorians permission to question the traditional views and dogma of established religions.

The argument Carlyle makes that might have helped allay Victorian anxiety is that doubt increases faith. Carlyle writes that readers can’t “call our Diogenes” wicked due to his crisis of faith because “unprofitable servants as we all are, perhaps at no era of his life was he more decisively the Servant of Goodness, the Servant of God, than even now when doubting God’s existence”. Carlyle contends that true faith requires challenge and that “a tearing down or questioning of the beliefs of one faith is in fact the preparation for a newer, richer, and truer form of belief in a new era” (Trela).

He gives Victorians permission to question their faith and to modify it for a new generation: “In every new era, too, such Solution comes out in different terms; and ever the Solution of the last era has become obsolete, and is found unserviceable. For it is man’s nature to change his Dialect from century to century; he cannot help it though he would” (Carlyle). Victorians embodied change and that spilled over into faith; as Amigoni states, “religious faith in a stable creation was never far from intellectual skepticism engendered by a sense of impermanence in Victorian society and culture” (Amigoni 6). For a society in the midst of tremendous change in all aspects of life, a society steeped in tradition, simultaneously hanging on to and rejecting ideologies of the past, permission to change must have been comforting.

Then again, even with the relieving messages in the text, Victorian society may not have benefitted from Sartor Resartus at all as it received a “bewildered reception with the audience of its day; neither Tories, Utilitarians, nor Whigs really understood it…due to Carlyle’s intentional disruption of the expectations of his British audience’s naïve realism” (Baker 225). Even if the text was understood by a broad audience, the Victorians never had a massive revival of faith, at least not to the “Everlasting Yea” extreme.

As with Victorian times, contemporary western societies may feel relief or even vindication at Carlyle’s contention that doubt is a path to a stronger faith. Doubt in a higher power permeates western culture as, again like with the Victorians, science continually answers those questions once put to God, and experience and humanity deny tenets of organized religious dogma once held fast. Also like the Victorians, contemporaries seem stuck at Doubt, never quite making it to the Everlasting Yea.

Works Cited

Amigoni, David. Victorian Literature. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011. Print.

Baker, Lee C. R. “The Open Secret of “Sartor Resartus”: Carlyle’s Method of Converting His Reader”. Studies in Philology 83.2 (Spring 1986): 218-235. Web. 8 Mar. 2016.

Carlyle, Thomas. Sartor Resartus. eBooks@Adelaide. The University of Adelaide. Web. 6 March 2016.

Trela, D.J. "Carlyle, Thomas 1795-1881." Encyclopedia of Life Writing: Autobiographical and Biographical Forms. Ed. Margaretta Jolly. London: Routledge, 2001. Credo Reference. Web. 8 Mar. 2016.

29 April 2016

Protagonists are not Always Good

In my Introduction to Literature course, one of the first things we learn are the elements of plot, specifically protagonist, antagonist, internal and external conflict, and Freytag's Triangle. I argue that they need to understand what happened before they can delve into why it all happened.

When we start talking about protagonists and antagonists, they immediately tell me it's good guys and bad guys. I don't know who is teaching it this way in high school (grade school?), but I want to find this person and have a nice sit-down with him or her. This idea is so ingrained in their heads that I swear half of them still are running with it at the end of the semester despite my continual protests and awesome handouts.

Just so we are all on the same page:

So at its most traditional, Harry Potter is a protagonist and Lord Voldemort is an antagonist. Harry being all "I want a normal life" and Voldemort being all "I must kill you Harry" which, obviously, prevents Harry from that normal life fantasy. This is an example of a traditional external conflict.

But not all books follow such a traditional structure. For example, some stories have internal conflicts where the protagonist and antagonist are the same person. Think Hamlet and his non-stop pontificating over what he should do about his father's murder. It's Hamlet v. Hamlet ladies and gentleman.

Also, a pro does not have to be a good person. Actually a pro can be a very, very, very bad person like in American Psycho or Lolita. Here are 18 more books with nasty protagonists if you are interested.

Who do you think they left off the list? Who are your favorite bad guy protagonists?

When we start talking about protagonists and antagonists, they immediately tell me it's good guys and bad guys. I don't know who is teaching it this way in high school (grade school?), but I want to find this person and have a nice sit-down with him or her. This idea is so ingrained in their heads that I swear half of them still are running with it at the end of the semester despite my continual protests and awesome handouts.

Just so we are all on the same page:

Protagonist: main character

Antagonist: person or thing that works against the protagonist

So at its most traditional, Harry Potter is a protagonist and Lord Voldemort is an antagonist. Harry being all "I want a normal life" and Voldemort being all "I must kill you Harry" which, obviously, prevents Harry from that normal life fantasy. This is an example of a traditional external conflict.

But not all books follow such a traditional structure. For example, some stories have internal conflicts where the protagonist and antagonist are the same person. Think Hamlet and his non-stop pontificating over what he should do about his father's murder. It's Hamlet v. Hamlet ladies and gentleman.

Also, a pro does not have to be a good person. Actually a pro can be a very, very, very bad person like in American Psycho or Lolita. Here are 18 more books with nasty protagonists if you are interested.

Who do you think they left off the list? Who are your favorite bad guy protagonists?

26 April 2016

Traditional Wins in Early American Lit

I recently posted a review of Henry James's Daisy Miller in which I remarked that the overall plot of the novella suggests that the traditional views of acceptable behavior and thought win out over the progressiveness of American culture. The novella challenges the status quo through the character of Daisy, who we are clearly supposed to identify with, and yet her comeuppance is quite drastic, suggesting a less-than-stellar recommendation for defying tradition.

Possibly the most remarkable example of the traditional or dominant culture winning in early American Lit is the story of Phillis Wheatley, a slave living in the mid-1800s. While the white family she - quite literally - belonged to is alive, Wheatley enjoys a privileged position in society, even traveling to Europe and socializing with aristocracy and dignitaries. When that family passes, however, Wheatley loses her status and eventually dies in abject poverty. Despite being renowned in the Western world as a great poet, the American public refused to support Wheatley.

It is arguable that the dominant culture, white American culture, won out long before Wheatley's fall to poverty and eventual death. Wheatley's acclimation to white America was astounding, she even went so far as to write the following in one of her poems:

"'Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there's a God".

She believes that her arrival in Western culture which brought her to Christianity is a blessing despite the fact she was kidnapped and sold into slavery. For a modern reader, this is, I think, rather distasteful; although she does lighten the horror by using this opening as a way to introduce the idea that while "some view our sable race with scornful eye" Americans need to know that "Negros, black as Cain, / May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train". Still, by saying that African-Americans need to be "refin'd" she is letting white American culture win.

Strangely Wheatley's life story and James's fictional one seem to contradict each other regarding the progressiveness of American and European society. In Daisy Miller, it is the Americans who are progressive; whereas the opposite is true in Wheatley's case. Europe would not countenance a female who disregarded the boundaries of her gender; America would not support an African-American who disregarded the boundaries of her race. This makes me want to read more works about the collision of European and American society in regards to gender and racial equality. Was Europe open to racial equality but bound and determined to deny women? Was America okay with progressive women but adamant against equality across race? If you have any suggestions on relevant books, I would love to hear them!

James and Wheatley both feature two cultures colliding, and it is clear that all parties are effected by the clash, but in all both cases, the dominant culture wins. Overall, do you think these authors are challenging the status quo or supporting it?

Possibly the most remarkable example of the traditional or dominant culture winning in early American Lit is the story of Phillis Wheatley, a slave living in the mid-1800s. While the white family she - quite literally - belonged to is alive, Wheatley enjoys a privileged position in society, even traveling to Europe and socializing with aristocracy and dignitaries. When that family passes, however, Wheatley loses her status and eventually dies in abject poverty. Despite being renowned in the Western world as a great poet, the American public refused to support Wheatley.

It is arguable that the dominant culture, white American culture, won out long before Wheatley's fall to poverty and eventual death. Wheatley's acclimation to white America was astounding, she even went so far as to write the following in one of her poems:

"'Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there's a God".

She believes that her arrival in Western culture which brought her to Christianity is a blessing despite the fact she was kidnapped and sold into slavery. For a modern reader, this is, I think, rather distasteful; although she does lighten the horror by using this opening as a way to introduce the idea that while "some view our sable race with scornful eye" Americans need to know that "Negros, black as Cain, / May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train". Still, by saying that African-Americans need to be "refin'd" she is letting white American culture win.

Strangely Wheatley's life story and James's fictional one seem to contradict each other regarding the progressiveness of American and European society. In Daisy Miller, it is the Americans who are progressive; whereas the opposite is true in Wheatley's case. Europe would not countenance a female who disregarded the boundaries of her gender; America would not support an African-American who disregarded the boundaries of her race. This makes me want to read more works about the collision of European and American society in regards to gender and racial equality. Was Europe open to racial equality but bound and determined to deny women? Was America okay with progressive women but adamant against equality across race? If you have any suggestions on relevant books, I would love to hear them!

James and Wheatley both feature two cultures colliding, and it is clear that all parties are effected by the clash, but in all both cases, the dominant culture wins. Overall, do you think these authors are challenging the status quo or supporting it?

19 April 2016

Americans and the Other

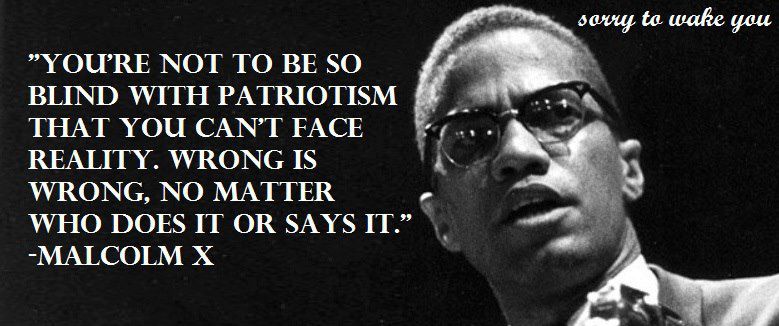

Nothing binds Americans together more than the foreign “Other”, especially in the context of war.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, I was tiredly sitting on the “L”, on my way to work in downtown Chicago. I didn’t make it two steps into my building when we were sent home for fear an attack on Chicago was imminent. Over the next year, I was impressed, frustrated, and disgusted by the American reaction to the tragedy. Patriotism skyrocketed, flags were flying everywhere, and Americans were joining together in solidarity. Well, Americans that didn’t look like the people who attacked the country anyway. Those Americans were being ostracized and demonized.

David Foster Wallace, in his article “9/11: The View from the Midwest”, really captures the feel of those days. When explaining the unity of Americans at the time, Wallace points out the strange truth about flags: “If the purpose of a flag is to make a statement, it seems like at a certain point of density of flags you’re making more of a statement if you don’t have one out” (Wallace). The sense that not joining in the unified display of patriotism was an indication of hating America or sympathizing with terrorists was very real. When threatened by an outside force, America joins together in an almost obsessive way, and there is certainly a negative reaction against those who do not join in the spectacle of unity.

Whitman, in “Over the Carnage Rose Prophetic a Voice” and “First O Songs for a Prelude”, discusses American unity in a much more positive light. Wallace’s undertones suggest a possible falsity to the displays of unity; he points out that his fear over not having a plastic flag is rather macabre when so many just died - the unity of the living subjugating the loss of the dead. Whitman’s discussion, however, proposes this unity is a favorable attribute.

In “Over the Carnage Rose Prophetic a Voice,” Whitman argues that the only way for peace and freedom to flourish is through love. I think his poem would have been useful in the days after 9/11. Arguing that “the continuance of Equality shall be comrades”, Whitman’s words may have discouraged the rampant hatred that sprung up against the Middle East, against Muslims, against anyone who looked in any way like the terrorists.

Whitman again addresses this unity in his poem “First O Songs for a Prelude” which is about the way his community quickly “threw off the costumes of peace with indifferent hand” to join in the war. He speaks of all the men, listing various jobs they have, leaving to fight, arming themselves, “blood up”. The men join together in arms, the mothers sadly, worriedly support their sons' decision to join, all are working together towards the united front.

In “Over the Carnage Rose Prophetic a Voice”, Whitman says “affection shall solve the problems of freedom yet”, and I certainly hope this is true. This theme of Americans joining together in solidarity – whether to fight or to support the fighters - seems common in American war literature.

Obviously patriotism is still alive and well in America today, but do you think the extremes of it are actually polarizing the country?

On the morning of September 11, 2001, I was tiredly sitting on the “L”, on my way to work in downtown Chicago. I didn’t make it two steps into my building when we were sent home for fear an attack on Chicago was imminent. Over the next year, I was impressed, frustrated, and disgusted by the American reaction to the tragedy. Patriotism skyrocketed, flags were flying everywhere, and Americans were joining together in solidarity. Well, Americans that didn’t look like the people who attacked the country anyway. Those Americans were being ostracized and demonized.

David Foster Wallace, in his article “9/11: The View from the Midwest”, really captures the feel of those days. When explaining the unity of Americans at the time, Wallace points out the strange truth about flags: “If the purpose of a flag is to make a statement, it seems like at a certain point of density of flags you’re making more of a statement if you don’t have one out” (Wallace). The sense that not joining in the unified display of patriotism was an indication of hating America or sympathizing with terrorists was very real. When threatened by an outside force, America joins together in an almost obsessive way, and there is certainly a negative reaction against those who do not join in the spectacle of unity.

Whitman, in “Over the Carnage Rose Prophetic a Voice” and “First O Songs for a Prelude”, discusses American unity in a much more positive light. Wallace’s undertones suggest a possible falsity to the displays of unity; he points out that his fear over not having a plastic flag is rather macabre when so many just died - the unity of the living subjugating the loss of the dead. Whitman’s discussion, however, proposes this unity is a favorable attribute.

In “Over the Carnage Rose Prophetic a Voice,” Whitman argues that the only way for peace and freedom to flourish is through love. I think his poem would have been useful in the days after 9/11. Arguing that “the continuance of Equality shall be comrades”, Whitman’s words may have discouraged the rampant hatred that sprung up against the Middle East, against Muslims, against anyone who looked in any way like the terrorists.

Whitman again addresses this unity in his poem “First O Songs for a Prelude” which is about the way his community quickly “threw off the costumes of peace with indifferent hand” to join in the war. He speaks of all the men, listing various jobs they have, leaving to fight, arming themselves, “blood up”. The men join together in arms, the mothers sadly, worriedly support their sons' decision to join, all are working together towards the united front.

In “Over the Carnage Rose Prophetic a Voice”, Whitman says “affection shall solve the problems of freedom yet”, and I certainly hope this is true. This theme of Americans joining together in solidarity – whether to fight or to support the fighters - seems common in American war literature.

Obviously patriotism is still alive and well in America today, but do you think the extremes of it are actually polarizing the country?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)